Growing up with five siblings in a Pacific Northwest United States family that supported exploration, multicultural exposure, knowledge of current world affairs, creativity, scientific and religious education, Olympia, WA-based sculptor Ross Matteson’s life has always included some form of adventure and imaginative experimentation. In 2016, Ross purchased 1,600 pound custom cut block of Belgian Black marble from ABC Stone. His aim: to create on commission a large plate-shaped sculpture depicting a duck hunt.

Growing up with five siblings in a Pacific Northwest United States family that supported exploration, multicultural exposure, knowledge of current world affairs, creativity, scientific and religious education, Olympia, WA-based sculptor Ross Matteson’s life has always included some form of adventure and imaginative experimentation. In 2016, Ross purchased 1,600 pound custom cut block of Belgian Black marble from ABC Stone. His aim: to create on commission a large plate-shaped sculpture depicting a duck hunt.

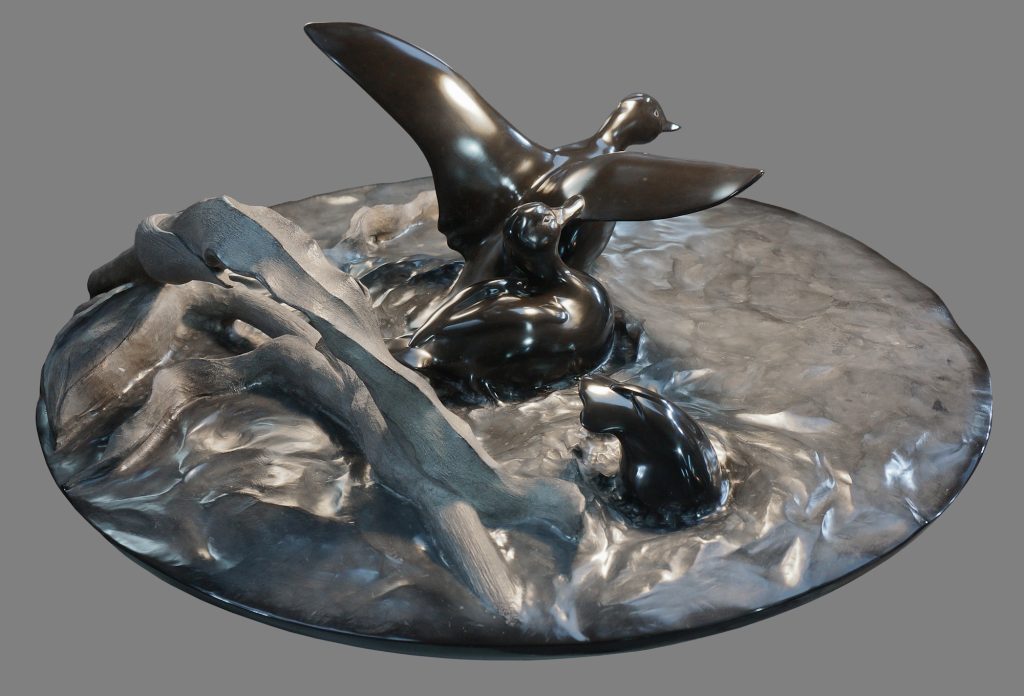

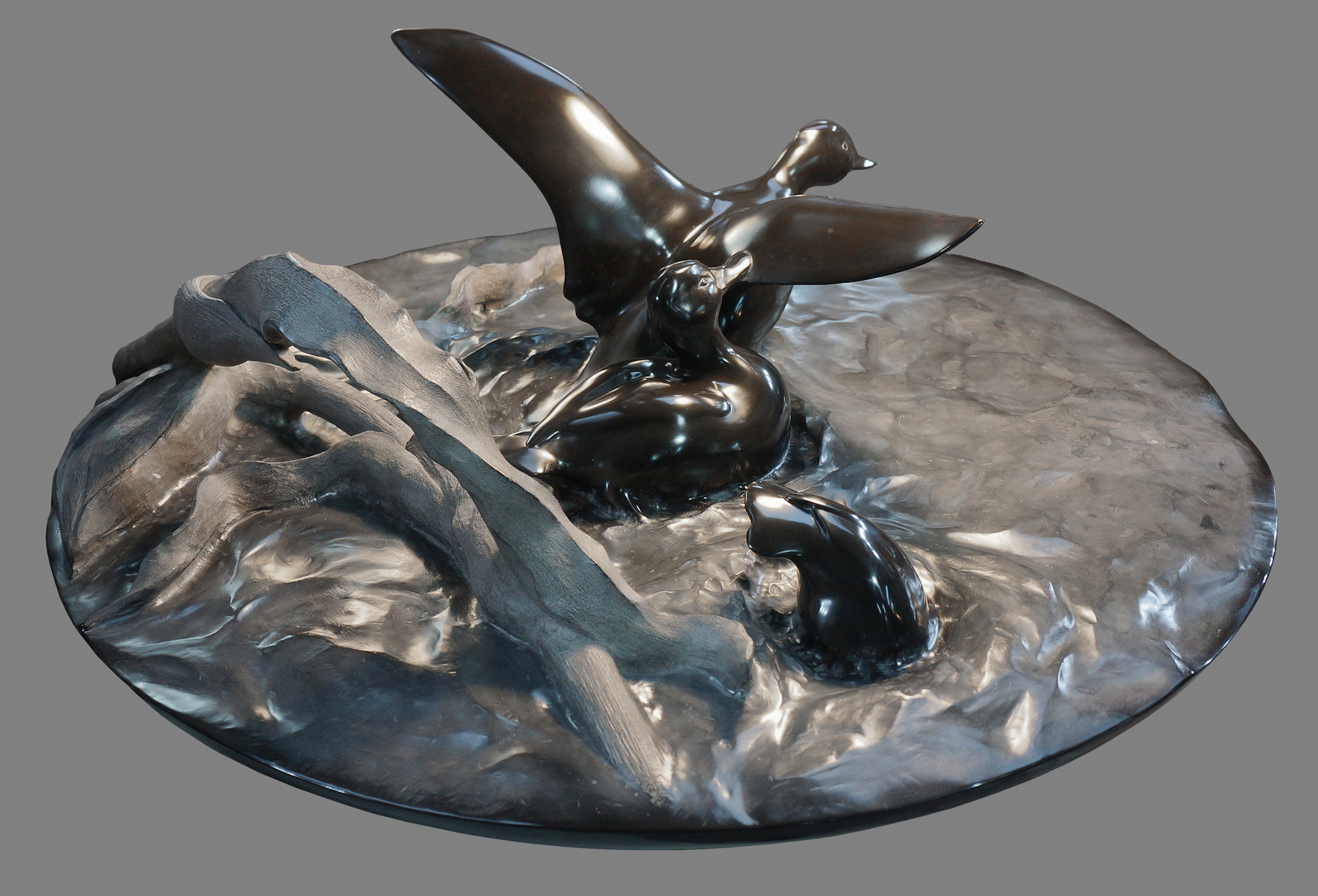

After familiarizing himself with the particular species of duck endemic to the area in which the finished sculpture would be displayed, observing and taking thousands of photographs of the bird, and consulting with duck hunters, Ross set to work on his project. Using both CNC and traditional sculpting tools, he produced his sculpture: Peregrine’s Plate.

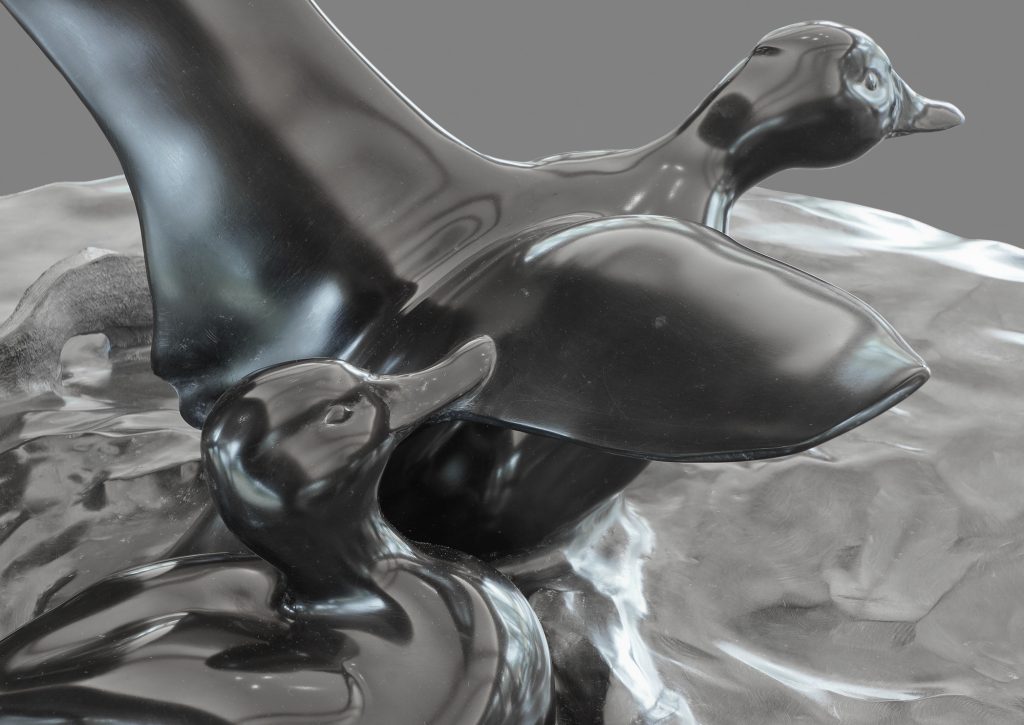

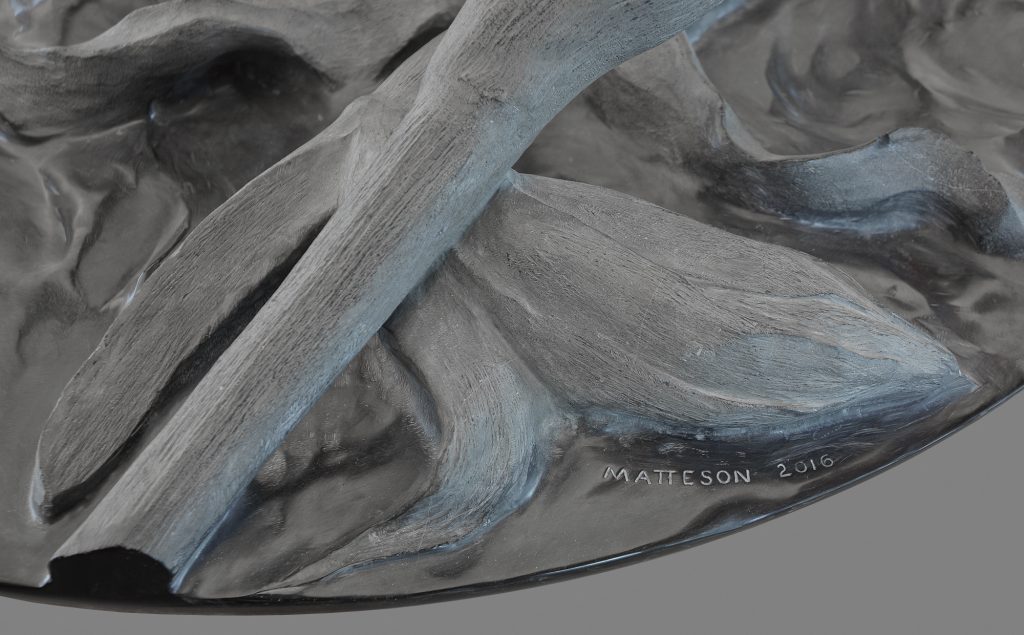

The density and integrity of ABC’s marble was up to the challenge of what might be regarded as a “pushing” of the material: the finished weight of the sculpture is four-hundred pounds, but it is exquisitely finely wrought and delicate. “After it was complete,” says Ross, “when I tapped lightly on each open wing of the central bird in the composition with my finger, they rang like bells! There was even a beautiful harmonic resonance between the two. Fortunately, everyone else had the wisdom not to even get close to touching those wings!”

We recently had a chance to speak with Ross about Peregrine’s Plate, his career as a sculptor, his creative process, and how he came to select ABC’s Belgian Black marble for this project. (Read to the very end for a photo gallery documenting the fascinating process through which Ross created his sculpture!)

ABC Stone: How would you describe yourself?

Ross Matteson: I like to think of myself as a community builder, often using visual art to help bring people together around shared values. I am fearless about addressing big issues (social equality; politics; religion; education; the environment; agriculture) and seeking originality, beauty and potential where others may not.

ABC: When did you begin making sculptures?

RM: From childhood. Full-time, professionally: from 1987.

ABC: How did you determine the size and density of the block you would need, and how did you decide upon the material Belgian Black.

RM: A finished, quality piece of this marble can look like black glass, only with an organic lifelike warmth about it. It is a rare, beautiful and prestigious material. The site specific requirements of this particular indoor entryway sculpture dictated the dimensions. I was blessed with clear renderings of an exquisite architectural setting along with an intelligent plan to place a sculptural focal point just inside the doorway on a predetermined round table. I knew that the table would be seven feet in diameter, allowing for me to propose a centered, relatively delicate “subject relevant” concept of a smaller diameter to the broker and client. The line of sight through the building from the front door looks out onto a beautiful landscape, including a large migratory duck pond. The logical subject, in this context, was three ring-necked ducks in a flooded corn field where much of the collector’s duck hunting occurs.

The narrative in the visually active composition that I imagined is that these ducks are panicking and moving in response to a natural predator. I decided that this unseen predator was to be a peregrine falcon since, as a falconer, I hunt ducks with peregrine falcons and am familiar with the defense behavior of ducks when falcons are above them. One of my ducks had to be taking flight with his wings up to add drama to my story while honoring, and not blocking, the beautiful view through the glass walls to the pond and landscape. I knew that to carve thin wings of a duck, on the upstroke, would necessitate a very dense and reliable block of stone, and a lot of removed stone. The challenge was that I didn’t know if this larger block of stone that would be required was available, or if it even existed. My proposal was contingent on finding a supplier with a very high level of confidence and integrity.

ABC: How long did it take to create the sculpture?

RM: This is always a difficult question and some sculptors I know give their age when asked! I was first approached with this opportunity in February of 2016. A contract was finalized in April. My custom quarried and cut stone was ordered in May, arrived in September, and the finished piece was delivered in December. I would have preferred a year of carving time, but this true for all my pieces

ABC: How did you learn about ABC Stone?

RM: I did an exhaustive internet search for existing Belgian Black marble blocks of the desired size, without success. An intern of mine asked Jonathan LaFarge, her former instructor at the Carving Studio and Sculpture Center in West Rutland, Vermont, for ideas. He referred me to ABC Stone, and you, fortunately, have direct access to the Belgian Black quarry.

When I first got involved with the possibility of buying this really expensive piece of stone, I was pretty uncomfortable. If the stone hadn’t proved to be the right density and integrity for my purposes, this would have been a huge liability. My daughter happened to be in New York at the time and I sent her to meet Ken at ABC after he and I began to correspond. She attended one of your events and was treated very nicely and, frankly, this was an important part of me doing business with ABC Stone. (*laughs*)

ABC: Why do you feel that your sculpture constituted a “pushing” of the material?

RM: Belgian Black is hard, brittle and expensive. A poorly chosen stone has been described by one of my colleagues as “downright explosive.” It just so happens that the meaning and “action” in my piece is explosion/panicked/moving—but not in pieces on the floor! Bringing visual motion to a cohesive inanimate object is a simple idea but difficult goal. One of the ways I approach visual motion in the poses and lyricism of my compositions is by staying alert to the difference between “potential motion” and “frozen motion.” I think that many artists would agree that elegance can require a high level of craftsmanship. There was no room for error in executing this piece given some of the thin, polished and unsupported forms.

Much of my carving time was spent in thought or in conducting tests. I had to pre-engineer what tools to use along the sequence of cutting and polishing my stone. Open wings and extended heads all had posts or bridges of stone connected to them until the very last part of the carving process. In addition, an elaborate device was invented for lifting the finished sculpture.

ABC: Would you give us a rundown of your creative process?

RM: Most of what I really do when carving a sculpture is to stare at both the material and reference and just think. I am always learning about the vastness of a three-dimensional surface. I am not satisfied easily and my self-critique is brutal, but usually very internal and private. Memories sometimes help synthesize a needed refinement or satisfaction with what is there. In other words, I trust a memory of how an escaping duck made me feel more than a video, photograph, or taxidermied reference. The reason is simple: a feather is not a piece of marble. Everything needs to work with the time, materials, tools, lighting and experience at hand. Being around people such as Ken, the art broker, the architect, or the collector on this project, who are passionate about a subject, material, or tool that I am working with, is a crucial part of the community responsible for helping bring my original ideas to light. On a piece like Peregrine’s Plate, I initially sculpt a maquette as reference. In this project, it was very helpful to create a life-sized model.

I work to understand the potential of each material I use and, as I mentioned, also enjoy support from family, a rich network of colleagues, subcontractors, and suppliers that rally around unique ideas worthy of community support. Distracted, childlike observations of the world around me continually spawn metaphors. One example is an intersecting wave pattern in front of a swimming Bufflehead duck resting in a sculpture titled Ripple Effect. Another example, in Peregrine’s Plate, is the drake’s opening wings thoughtlessly knocking the hen’s head to the side in the panic of the escape. I think that such metaphors, often inspired by the natural world, come to light because I care about their relevance to humanity. I love making site-specific art that may be sensitive to design factors in a commission, but which is also inspiring to me, relevant over time, and draws from a choice of incredibly rich and diverse permanent media available. Of course, making anything to last for centuries—let alone, to be cared about by generations of owners—is a pretty good challenge!

“Enduring grace” is a signature goal of mine. It transcends cliché art categories such as “wildlife artist,” or “contemporary artist,” and can better represent any art that is unique, but meaningful across both time and culture. Over many centuries, Belgian Black marble has already proved its cross-cultural appeal. In the finished sculpture, Peregrine’s Plate, it was structurally and aesthetically foundational to my goal of expressing what I hope will be considered relevant, beautiful, and graceful over many years.

Peregrine’s Plate (2016)

by Ross Matteson

Olympia, WA

Belgian Black marble

37” diameter by 14” high

private collection

photos courtesy of Matteson Sculpture Studio

Transitioning from the music recording industry, which was his first career path after graduating from the Evergreen State College, Ross has been practicing sculpture for the last thirty-one years, and has had his work appear in over 150 shows. His sculptures are in the permanent collections of, or have been exhibited in, such museums as the Woodson Art Museum (Wausau, WI), the National Museum of Wildlife Art (Jackson, WY), the Gilcrease Museum (Tulsa, OK), the Natural History Museum (London, United Kingdom), the National Cowboy and Western Heritage Museum (Oklahoma City, OK), the Bennington Center for the Arts (Bennington, VT), and other museums around the country for shows sponsored by the “Society of Animal Artists” (New York, NY), and in numerous commercial galleries, and private, corporate and public collections around the world.

To learn more about Ross, and his work, visit mattesonsculpture.com.

-

Ross Matteson with peregrine falcon, a bird historically referred to as a 'duck hawk'.

Ross Matteson with peregrine falcon, a bird historically referred to as a 'duck hawk'. -

The 'ring'necked duck on water' is inspiration for Peregrine's Plate.

The 'ring'necked duck on water' is inspiration for Peregrine's Plate. -

Matteson sculpts a life'sized wax reference model on a circular wooden support form cut from the same digital CNC file as the marble.

Matteson sculpts a life'sized wax reference model on a circular wooden support form cut from the same digital CNC file as the marble. -

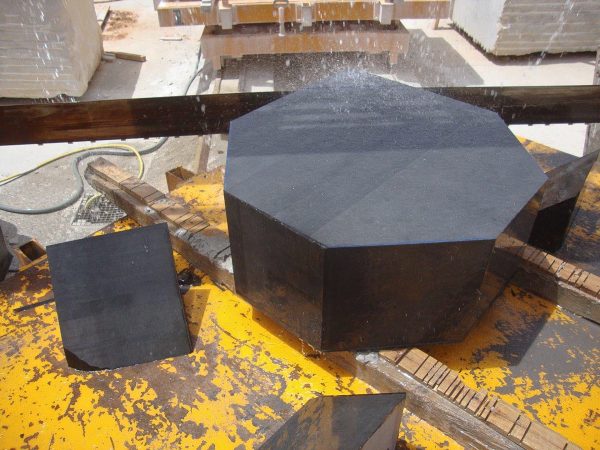

A massive quarried block of Belgian Black marble is carefully assessed in Portugal, for its purest, 'sculpture quality' core. The dense heart of this stone is then cut and polished to the artists specifications.

A massive quarried block of Belgian Black marble is carefully assessed in Portugal, for its purest, 'sculpture quality' core. The dense heart of this stone is then cut and polished to the artists specifications. -

A massive quarried block of Belgian Black marble is carefully assessed in Portugal, for its purest, 'sculpture quality' core. The dense heart of this stone is then cut and polished to the artists specifications.

A massive quarried block of Belgian Black marble is carefully assessed in Portugal, for its purest, 'sculpture quality' core. The dense heart of this stone is then cut and polished to the artists specifications. -

A massive quarried block of Belgian Black marble is carefully assessed in Portugal, for its purest, 'sculpture quality' core. The dense heart of this stone is then cut and polished to the artists specifications.

A massive quarried block of Belgian Black marble is carefully assessed in Portugal, for its purest, 'sculpture quality' core. The dense heart of this stone is then cut and polished to the artists specifications. -

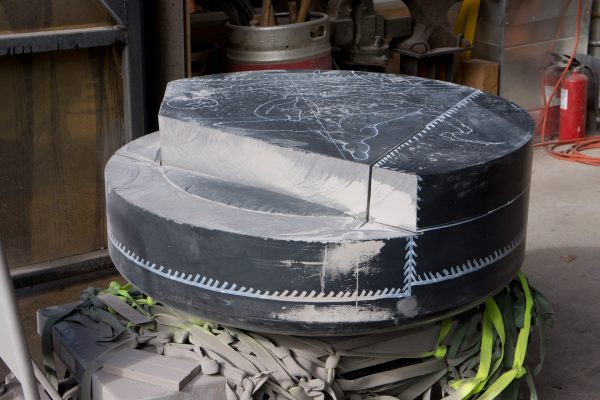

After traveling half way around the world to the sculptor's studio in Olympia, Washington, the polished domed end of the 1600 pound cylinder is inverted, and becomes the under'side of Peregrine's Plate.

After traveling half way around the world to the sculptor's studio in Olympia, Washington, the polished domed end of the 1600 pound cylinder is inverted, and becomes the under'side of Peregrine's Plate. -

After stone is removed in the largest sections possible, more nuanced shaping begins.

After stone is removed in the largest sections possible, more nuanced shaping begins. -

After stone is removed in the largest sections possible, more nuanced shaping begins.

After stone is removed in the largest sections possible, more nuanced shaping begins. -

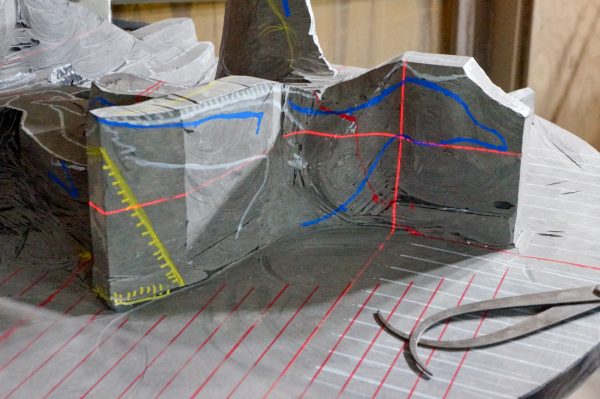

The artist uses different color markers to map out his cuts. While the form is being blocked out, elevation and x/y axis reference marks are sometimes keyed to transparent templates with calibrated lasers shining through them onto the stone.

The artist uses different color markers to map out his cuts. While the form is being blocked out, elevation and x/y axis reference marks are sometimes keyed to transparent templates with calibrated lasers shining through them onto the stone. -

The artist uses different color markers to map out his cuts. While the form is being blocked out, elevation and x/y axis reference marks are sometimes keyed to transparent templates with calibrated lasers shining through them onto the stone.

The artist uses different color markers to map out his cuts. While the form is being blocked out, elevation and x/y axis reference marks are sometimes keyed to transparent templates with calibrated lasers shining through them onto the stone. -

During the power tool phase of the project, many different sizes and types of diamond cutting wheels, burrs and abrasives are used on gas, electric and pneumatic angle grinders and die grinders.

During the power tool phase of the project, many different sizes and types of diamond cutting wheels, burrs and abrasives are used on gas, electric and pneumatic angle grinders and die grinders. -

Delicate portions of the composition are temporarily supported with marble bridges anchored to the support form. After the wings, head and neck are polished, the supports are then carefully removed. Florescent orange earplugs are taped to the wings as a cautionary measure.

Delicate portions of the composition are temporarily supported with marble bridges anchored to the support form. After the wings, head and neck are polished, the supports are then carefully removed. Florescent orange earplugs are taped to the wings as a cautionary measure. -

Delicate portions of the composition are temporarily supported with marble bridges anchored to the support form. After the wings, head and neck are polished, the supports are then carefully removed. Florescent orange earplugs are taped to the wings as a cautionary measure.

Delicate portions of the composition are temporarily supported with marble bridges anchored to the support form. After the wings, head and neck are polished, the supports are then carefully removed. Florescent orange earplugs are taped to the wings as a cautionary measure. -

Delicate portions of the composition are temporarily supported with marble bridges anchored to the support form. After the wings, head and neck are polished, the supports are then carefully removed. Florescent orange earplugs are taped to the wings as a cautionary measure.

Delicate portions of the composition are temporarily supported with marble bridges anchored to the support form. After the wings, head and neck are polished, the supports are then carefully removed. Florescent orange earplugs are taped to the wings as a cautionary measure. -

Delicate portions of the composition are temporarily supported with marble bridges anchored to the support form. After the wings, head and neck are polished, the supports are then carefully removed. Florescent orange earplugs are taped to the wings as a cautionary measure.

Delicate portions of the composition are temporarily supported with marble bridges anchored to the support form. After the wings, head and neck are polished, the supports are then carefully removed. Florescent orange earplugs are taped to the wings as a cautionary measure. -

Matteson hand sands the top of a duck bill, with careful counter'pressure from underneath.

Matteson hand sands the top of a duck bill, with careful counter'pressure from underneath. -